Jewish Resistance in Hungary

Victims of the Holocaust are often blamed for yielding to the genocide like "sheep in the slaughterhouse" instead of standing up against their murderers. In Hungary from 1944 to 1945, conditions were not in place for armed Jewish resistance: the majority of potential fighters were not present, there was insufficient time to organise a movement, and there were no weapons or non-Jewish resistance movements that could have assisted Jews. Therefore the Zionists, who performed organised resistance, did not take up arms, but followed the tactics of bribery, hiding and forging in their battle against Hungarian and German Nazis.

Click here to read more about the Holocaust in Hungary.

Almost without exception, young and healthy Jewish men of fighting age were in labour-service camps under tight military guard.

|

Young man able to take up arms were in labour service units |

The destruction of the Hungarian Jews became the fastest "dejewification" program executed in the history of the Holocaust. Events unfolded at a breathtaking speed. The disenfranchisement and despoliation of the Jews was carried out within weeks, the ghettoisation began already on the 29th day after the German occupation, mass deportations followed within four weeks and were over in 56 days. The organisers of the Warsaw ghetto uprising (a total of 700 to 1000 young men and women in good physical condition) took up arms in the third year of the ghetto's existence, while the ghetto standing for the longest time in Hungary (the one in Budapest) lasted but seven weeks.

In some other parts of Europe, revolting Jews could count on the support of local resistance movements to varying degrees, while in Hungary there was no substantial Gentile armed resistance that could have offered assistance to a potential Jewish-led uprising. In contrast to the armies of Yugoslavia, France or Poland, the Hungarian army did not disintegrate and thus they did not leave behind large quantities of weapons and ammunitions to be used by a resistance movement. Potential Jewish fighting organisations could not count on the support of the hinterland either, similar to that received from Moscow by various irregular troops operating in occupied Soviet territories.

The majority of Hungarian Jews were law-abiding citizens. Most would never have contemplated refusing to obey the authorities of their native country, not to mention active resistance. Moreover, the situation of the Jews of Budapest, the last to remain intact by the end of 1944, fundamentally differed from those living in other East European territories. Urban uprisings in the East broke out when the Germans started the liquidation of the given ghetto (e.g., Warsaw, April 19, 1943; Bialystok, August 16, 1943; Czestochowa, January and June 25, 1943; Bedzin, August 1, 1943). The rebels were aware that their fate was sealed; the only question was whether they would perish fighting with arms in hand or in a death camp. In the winter of 1944/45 the Red Army was already besieging the capital, the defeat of the Nazis and the Arrow Cross was inevitable and thus the dilemma took a different form: to die fighting or survive playing for time.

Zionist Resistance in Hungary

Consequently, Jewish groups that organised to defy the program of genocide chose different paths of resistance: negotiations, bribery, forging documents, providing hiding and assisting refugees. For the most part, these responsibilities were taken on by Zionist organisations.

Between the two World Wars, Zionism was a political and ideological movement with minor presence and little influence in Hungary,

|

Zionist groups may be divided into two major categories: the "adults," who maintained good relations with international Zionist organisations (e.g., the Jewish Agency for Palestine), in some respects operating as their extension; and the more self-reliant and independent "youth"

(the Halutzim). These two large groups were connected by a number of personal and institutional ties, while simultaneously divided by many conflicts. The most prominent leader of the "adults" was Rezső Kasztner , who first held lengthy and still-debated negotiations with the Eichmannkommando and later with Reichsführer-SS Himmler's plenipotentiary, Kurt Becher. As a result of these talks and a payment of over 2 million US dollars, in late June around 1700 Hungarian Jews were allowed to leave for the safety of Switzerland through the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.[1]

The "young" Zionists, led by Márton Elefánt, Rafael Friedl, Perec Révész, Endre Grósz,

|

Zionist resister David Grósz masqueraded as an Arrow Cross man |

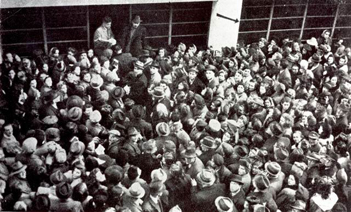

Between the end of July and the liberation, their headquarters was the "Glass House" in Vadász Street, Budapest. The story of the opening of the building for rescue purposes goes back to a Crown Council (Koronatanács - the joint council of the government and the Regent) held on June 26, when, under international pressure, Regent Miklós Horthy and the government gave its blessing for the emigration of some 7000 Hungarian Jews.[4] The largest share of the quota was assigned to neutral Switzerland, which also represented countries at war with Hungary. Swiss Deputy Consul Carl Lutz had the responsibility to draw up the list of emigrants, and the glass wholesaler Artúr Weiss offered his Vadász Street property for the operation.[5] At the end of June the Swiss Embassy opened its emigration office there, which, with Lutz's full knowledge and support, within months became the young Zionists' hiding place, base of illegal operation and centre for the distribution of forged documents. Those on the emigration list received a certificate (a protective pass) stating they were listed on a "collective passport", which, in theory, exempted them from discriminating regulations, i.e., eventually from deportation. "The news spread like wild fire", remembered Márton Elefánt (Mose Pill), "Thousands, perhaps tens of thousands stood in front of 29 Vadász Street to get a protective pass, at times filling the entire street, bringing normal traffic to a standstill. Many, perhaps most, came risking their lives, staying on the line even during the hours of curfew for the Jews, and stood before the gate without wearing the yellow star."[6]

As the international recognition of his government was one of Szálasi's most essential foreign policy objectives,

[7] V. R. was first taken to the Óbuda brick factory and later to the concentration camp in Kaufering.The Zionists produced an increasing number of forged protective passes. According to Elefánt's recollection, "what we did was, we brought the forged papers to the embassy and issued them to those who did not get on the list containing 7800 names, or could not get such papers by other means. Later even this was insufficient, so we invented the bluff of a bluff. At 4 Perczell Mór Street we set up a thoroughly phoney embassy where we distributed high-quality counterfeits to applicants."[8] According to Artúr Weiss' wife, "Vadász Street not only worked as a Schutzpass factory, but it also became an asylum for administrators and their families, large numbers of labour camp deserters as well as many political activists, leading Social Democrats and communists". [9]

This could not remain a secret for long. "We lived in constant fear as it soon became evident that the building functioned

Masses in front of the Glass House on Vadász Street

not simply as an embassy, but a shelter for thousands", Mrs Weiss said in 1945. "Many people coming and going were seized on the street and soon the embassy building aroused the attention of the authorities."[10] According to Mihály Salamon, "the developments of December 31 did not come as a real surprise to leaders; firing submachine guns and lobbing hand grenades, an Arrow Cross detachment burst into the building. The assault resulted in three deaths and seventeen wounded, and it was by mere luck that we managed to save the people already lined up on the street from being deported by mobilizing the city's military and police high command."[11] However, the Arrow Cross returned the next day and they arrested and murdered Artúr Weiss, owner and director of the Glass House. Despite all of this, the majority of the residents lived to see the day of liberation.

Three young Palestinian Jews with Hungarian ancestry and who were fluent in Hungarian wrote a special chapter in the history of Zionist resistance. They arrived in the country in June as parachutists of the British Army to organise the protection of Hungary's remaining Jewish population and gather intelligence for the Allies. The utterly hopeless yet undoubtedly heroic undertaking claimed two of their lives. Hanna Szenes was arrested immediately as she crossed into Hungary along the southern border, and she was executed by the Arrow Cross in November. Two of her companions, Emil Nussbacher and Ferenc Goldstein were also nabbed. Nussbacher managed to escape from captivity, while Goldstein lost his life in a Nazi concentration camp.[12]

Footnotes

[1] Concerning the so-called "Kasztner case" see more in, for instance, Braham 1997, pp. 1023-1066 and Bauer 1994, pp. 145-260. About the Kasztner operation and its outcome, see Kádár-Vági, 2001, pp. 168-206, about the financial aspects of the transactions in the same place at pp. 211-219.

[2] Quoted by Ronén 1998, p. 33.

[3] On the activities of the Halutzim in detail see Cohen 2000, Ronén 1998, and Salamon and Benshalom 2001.

[4] Braham 1997, pp. 833-836.

[5] On Lutz' activities see also Tschuy 2002.

[6] Protocol 3619.

[7] Protocol 2054.

[8] Protocol 3619.

[9] Protocol 3598.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Protocol 3648.

[12] For Nussbacher's memoirs, see Palgi 2003.

References

Bauer 1994

Yehuda Bauer: Jews for Sale? Nazi-Jewish Negotiations, 1933-1945. New Haven and London, 1994, Yale University Press.

Benshalom 2001

Rafi Benshalom: We Struggled for Life. The Hungarian Zionist Youth Resistance during the Nazi Era. Jerusalem - New York, 2001, Gefen.

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Cohen 2002

Asher Cohen: A haluc ellenállás Magyarországon 1942-1944. (He-halutz Resistance in Hungary 1942-1944.) Budapest, 2002, Balassi.

Kádár-Vági 2001

Gábor Kádár - Zoltán Vági: Aranyvonat. Fejezetek a zsidó vagyon történetéből. (Gold Train. Chapters from the History of the Jewish Wealth.) 2001, Budapest, Osiris.

Palgi 2003

Yoel Palgi: Into the Inferno. The Memoir of Jewish Paratrooper Behind Nazi Lines. 2003, New Brunswick- New Jersey - London - Rutgers University Press.

Ronén 1998

Ávihu Ronén: Harc az életért. Cionista (Somér) ellenállás Budapesten 1944. (Fight for Life. Zionist (Shomer) Resistance in Budapest 1944.) 1998, Budapest, Belvárosi.

Salamon

Mihály Salamon: "Keresztény" voltam Európában. (I was "Christian" in Europe.) Tel Aviv, Népünk Kiadó.

Tschuy 2002

Theo Tschuy: Becsület és bátorság. Carl Lutz és a budapesti zsidók. (Honor and Bravery. Carl Lutz and the Budapest Jews.) 2002, Miskolc, Well-PRess.